Symbols of Force in the American Civic Landscape

The Civic Square and Its Inversions

The American city was conceived as the antithesis of the garrison. Where European capitals grew around fortified keeps and royal compounds, American urban centers emerged from markets, harbors, and crossroads—places where strangers could meet under minimal rules and maximum opportunity. The downtown square, the courthouse steps, the commercial district: these spaces embodied a particular vision of social order based on voluntary association, public discourse, and the productive energy of competing interests finding equilibrium.

This civic architecture carries meaning beyond its practical functions. When Thomas Jefferson designed the University of Virginia around an open lawn rather than a walled quadrangle, when planners laid out Manhattan’s grid to maximize circulation rather than defensive positions, when cities built libraries and museums rather than armories as their most prominent public buildings, they were making arguments about the nature of legitimate authority. The message embedded in these spaces declared that power should be transparent, accessible, and accountable to those it governed.

The presence of military force in such spaces operates as a kind of semantic violence against these foundational assumptions. When armored vehicles occupy streets designed for commerce and conversation, when soldiers establish checkpoints where citizens once moved freely, when the apparatus of external war appears in the heart of the polis, the symbolic message overwhelms any practical justification. The city stops speaking the language of civic engagement and begins speaking the language of occupation.

This transformation cannot be dismissed as merely tactical or temporary. Symbols have their own political physics. They create social realities that persist long after the immediate circumstances that prompted their deployment have passed. The imagery of military occupation in American cities communicates something fundamental about the relationship between state and citizen, something that reshapes that relationship through the very act of being seen.

The Semiotics of Urban Space

Every city tells a story about power through its physical organization. The placement of buildings, the width of streets, the prominence of monuments—these elements constitute a kind of spatial grammar that shapes how inhabitants understand their role in the social order. American cities traditionally narrated a story of democratic capitalism: commercial activity as the primary organizing principle, public spaces designed for gathering and debate, government buildings impressive but accessible, with their doors opening onto streets where anyone might walk.

The insertion of military force into this narrative creates immediate cognitive dissonance. Streets designed for the flow of commerce and the rhythms of daily life suddenly host the machinery of war. Courthouse steps where citizens traditionally exercised their rights to petition and protest become staging areas for armed personnel. Public squares that once hosted farmers markets and political rallies transform into security perimeters patrolled by soldiers carrying weapons designed for battlefield use.

The visual disruption goes beyond mere inconvenience. When military vehicles park where delivery trucks once unloaded goods, when armed checkpoints replace informal gathering spots, when the tools of foreign intervention appear in domestic space, the city’s fundamental character shifts from welcoming to exclusionary, from open to controlled, from trusting to suspicious. The space itself begins to communicate that normal civic life has been suspended, that extraordinary measures have become necessary, that the ordinary citizen can no longer be trusted to navigate public space without military supervision.

This symbolic transformation operates independently of whatever practical security concerns might justify the military presence. Even if the deployment successfully prevents specific incidents, even if citizens report feeling safer, even if crime statistics improve, the deeper message remains: this city now requires occupation to function. The implications of that message extend far beyond immediate security considerations.

The Architecture of Democratic Life

American civic architecture evolved from specific assumptions about human nature and political organization. The founders, influenced by Enlightenment thinking about natural rights and representative government, designed public spaces that would cultivate civic virtue through participation rather than enforce compliance through coercion. The New England town meeting, the courthouse square, the public market—these institutions assumed that citizens could govern themselves through reasoned debate and voluntary cooperation.

The physical design of these spaces reflected those assumptions. Courthouses featured grand steps and columned entrances that invited public access and suggested the majesty of law derived from popular consent. City halls opened directly onto public squares where citizens could gather, speak, and be heard. Commercial districts mixed different classes and interests in productive proximity, creating what urbanist Jane Jacobs would later call the “ballet of the sidewalk”—the spontaneous social coordination that emerges when diverse groups share common space under minimal rules.

Military occupation inverts every element of this democratic spatial grammar. Armed checkpoints replace open access. Secured perimeters substitute for permeable boundaries. Surveillance and control mechanisms override the presumption of citizen autonomy. The physical environment stops teaching democratic habits and begins teaching subjects about their proper relationship to authority: keep your distance, follow instructions, accept monitoring, demonstrate compliance.

The change operates at both conscious and unconscious levels. Citizens navigating militarized urban space must constantly calculate risk, monitor authority figures, and adjust their behavior to avoid unwanted attention. These habits of deference and self-surveillance, learned in occupied civic space, inevitably influence how people relate to authority in other contexts. The city becomes a school for subjects rather than citizens.

Historical Echoes and Contemporary Realities

American cities have experienced military occupation before, but always as acknowledged departures from normal governance rather than routine security measures. Federal troops occupied Southern cities during Reconstruction, but this was understood as an exceptional intervention in a defeated region. National Guard units deployed during urban riots in the 1960s, but these interventions were explicitly temporary responses to extraordinary breakdowns of civil order.

Contemporary militarization of urban space operates differently. The weapons, vehicles, and tactics developed for foreign warfare have been gradually integrated into routine domestic policing through programs like the Pentagon’s 1033 Program, which transfers surplus military equipment to local law enforcement agencies. The result is the normalization of occupation aesthetics in ordinary civic life, where SWAT teams deploy for routine warrant service and armored vehicles patrol neighborhoods experiencing no active conflicts.

This gradual militarization has proceeded without the explicit political debates that accompanied previous episodes of military deployment in domestic space. Instead of emergency declarations and sunset clauses, the transformation has occurred through bureaucratic channels, equipment transfers, and training programs that have slowly shifted the visual and operational culture of urban law enforcement toward military models.

The absence of explicit political authorization for this transformation makes its symbolic impact more powerful, not less. When military occupation is declared as an emergency measure, it carries implicit promises of temporariness and exceptional justification. When military aesthetics become routine features of civic life, they communicate something more disturbing: this is the new normal, the permanent condition of American urban space.

The Psychology of Occupied Space

Living in occupied space changes people in ways that extend far beyond immediate compliance with military authority. The constant presence of armed force creates the “anticipatory conformity”—the tendency to modify behavior based on what authorities might want rather than what they have explicitly demanded. Citizens begin to police themselves, avoiding activities that might draw unwanted attention, limiting their movements to predictable patterns, withdrawing from public engagement that might be misinterpreted as suspicious.

This psychological shift represents a profound departure from the habits of mind that democratic citizenship requires. Democracy assumes that citizens will engage actively in public life, voice disagreements with authority, and participate in the messy process of collective decision-making. Occupied space teaches the opposite lessons: avoid notice, defer to armed authority, treat public space as dangerous rather than welcoming.

The learning occurs through direct experience rather than explicit instruction. Citizens navigating checkpoints, submitting to searches, observing military patrols develop embodied knowledge about their proper relationship to state power. They learn to read the signals that indicate compliance or resistance, to calculate the risks of various forms of public behavior, to internalize the presumption that they are potential threats requiring monitoring and control.

These lessons prove remarkably durable. Research on communities that have experienced military occupation shows that the psychological effects persist long after the military forces withdraw. People continue to avoid certain public spaces, limit their political expression, and maintain the defensive postures they developed during the occupation period. The symbolic violence of military presence creates lasting changes in civic culture that cannot be easily reversed through policy pronouncements or public relations campaigns.

The transformation affects not just individual psychology but collective social patterns. Communities under military occupation typically experience declining participation in civic organizations, reduced attendance at public meetings, and increased social fragmentation as people withdraw into private spaces they perceive as safer. The civic life that democratic theorists consider essential to legitimate governance withers under the pressure of constant surveillance and the implicit threat of force.

The Erosion of Civic Trust

Perhaps the most profound impact of urban militarization lies in its effect on the social trust that makes democratic governance possible. Democracy requires citizens to believe that political conflicts can be resolved through persuasion rather than force, that authorities will respect constitutional constraints on their power, and that participation in civic life carries acceptable risks rather than potential threats to personal safety.

Military occupation of civic space undermines each of these foundational beliefs. When armed force becomes a visible feature of ordinary political life, it suggests that persuasion has failed as a mechanism for social coordination. When military equipment and tactics are deployed against domestic populations, it implies that constitutional constraints have become insufficient to maintain order. When citizens must navigate armed checkpoints to participate in civic activities, it signals that such participation now carries substantial personal risks.

The erosion occurs gradually and often below the threshold of conscious recognition. Citizens may not explicitly decide to withdraw from civic life, but they find themselves attending fewer public meetings, avoiding demonstrations, limiting their political expression to safer channels. The cumulative effect is a hollowing out of democratic culture even as democratic institutions formally continue to function.

This dynamic helps explain why military occupation often produces the opposite of its intended effects. While deployed to restore order and confidence, military presence in civic space frequently generates increased tension, reduced cooperation with authorities, and deeper social divisions. The symbolic message of occupation overwhelms any practical security benefits, creating new forms of instability rooted in legitimacy crises rather than criminal activity.

The American city, reimagined as an occupied space, stops functioning as a laboratory for democratic life and becomes instead a theater for the display of state power. The transformation carries implications that extend far beyond immediate security concerns, reshaping the fundamental relationship between citizen and state in ways that may prove more consequential than whatever specific threats prompted the military deployment in the first place.

The Imperial Mirror and Domestic Reflection

The American military has spent decades perfecting the choreography of occupation in distant lands. From Baghdad’s Green Zone to Kabul’s diplomatic quarter, from the checkpoints of the West Bank to the forward operating bases of sub-Saharan Africa, American forces have developed a sophisticated visual vocabulary for projecting power in contested territories. The imagery is unmistakable: armored convoys moving through urban streets, soldiers in battle gear manning security perimeters, helicopter patrols circling overhead, and the careful segregation of secure zones from the broader population.

This operational template carries embedded assumptions about the relationship between occupying force and occupied population. The military presence signals that normal governance has broken down, that local authorities cannot maintain order, that external intervention has become necessary to prevent chaos. The visual symbols communicate a clear hierarchy: those with weapons and armor possess legitimate authority, while unarmed civilians represent potential threats requiring constant monitoring and control.

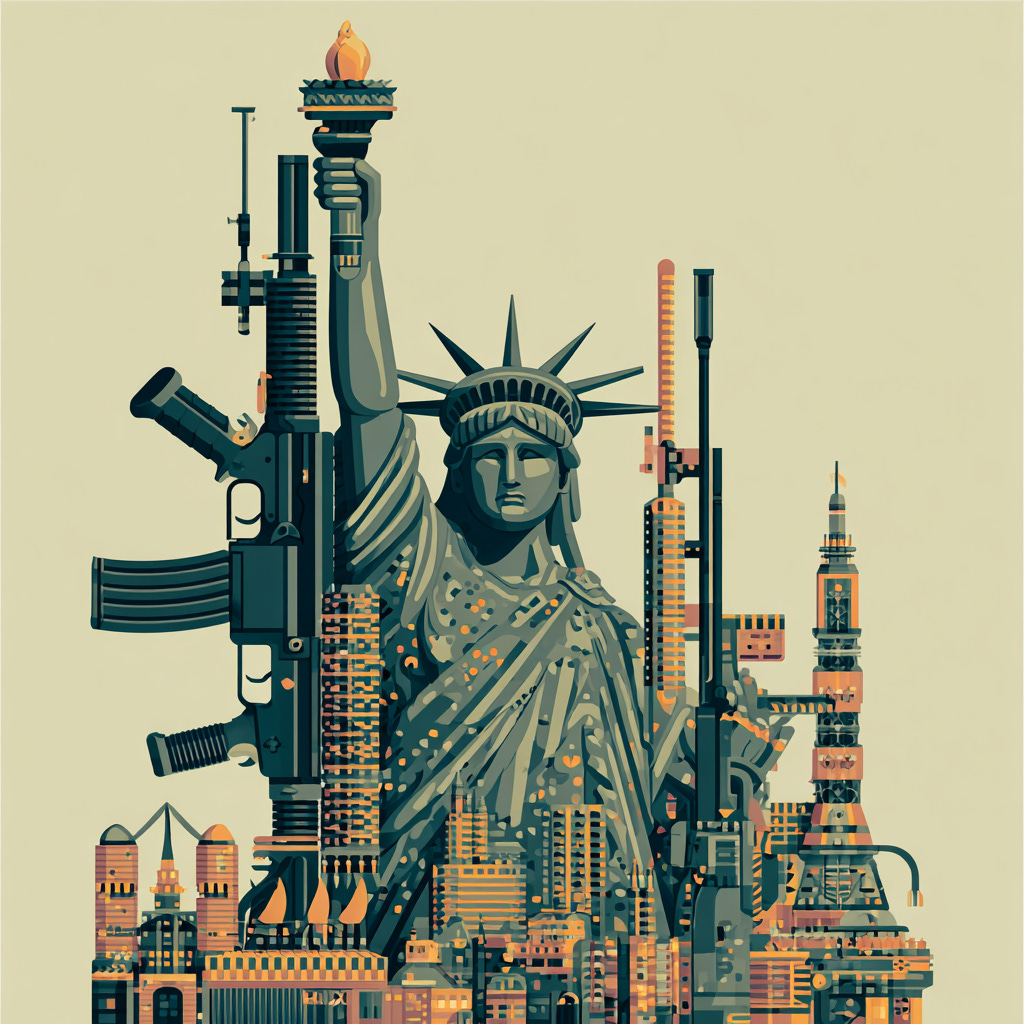

When this same symbolic apparatus appears in American cities, it imports these assumptions about political relationships into domestic space. The military equipment, tactical formations, and operational procedures that mark foreign occupation inevitably carry the same meaning when deployed against American populations. The semiotics of empire, reflected back into the imperial center, transform citizens into subjects and civic spaces into territories requiring pacification.

The Vocabulary of Imperial Control

American military doctrine has evolved sophisticated methods for establishing control in hostile urban environments. The tactical manual speaks of “population control measures,” “area denial operations,” and “deterrent patrols”—clinical language for the systematic intimidation of civilian populations through visible displays of overwhelming force. The goal is not merely to prevent specific criminal acts but to establish psychological dominance that discourages resistance before it can organize.

These techniques rely heavily on visual impact. Armored vehicles serve purposes beyond transportation; their presence on city streets communicates that normal civilian authority has been superseded by military command. Soldiers in full battle gear perform functions beyond crowd control; their visibility establishes that the rules of engagement have shifted from civilian law enforcement to military operations. Helicopter overflights accomplish tasks beyond surveillance; their sound and presence remind ground-level populations that they are being watched from above by forces possessing overwhelming tactical advantages.

The effectiveness of these techniques in foreign operations has been extensively documented. Populations subjected to such displays typically reduce their public activities, limit their political expression, and modify their daily routines to avoid unwanted encounters with military forces. The psychological pressure of constant surveillance and the implicit threat of overwhelming retaliation create what military strategists call “deterrent effects” that extend far beyond the immediate presence of armed forces.

American cities experiencing military deployment witness identical population responses. Residents avoid certain neighborhoods, cancel public gatherings, and restrict their movements to predictable patterns that minimize contact with military personnel. The behavioral changes occur regardless of whether citizens support or oppose the military presence, suggesting that the intimidation operates at psychological levels deeper than conscious political calculation.

Zones of Exception, Zones of Control

Imperial operations typically involve the creation of distinct zones with different rules, different populations, and different relationships to authority. The Green Zone in occupied Baghdad exemplified this spatial segregation: a heavily fortified area where normal civilian life continued under military protection, surrounded by red zones where different rules applied and different dangers prevailed. The psychological effect of such spatial divisions extends beyond mere security considerations to reshape how entire populations understand their relationship to legitimate authority.

Similar spatial dynamics emerge when American cities experience military occupation. Secured perimeters around government buildings create green zones where normal civic activities can continue under military oversight. The areas beyond these perimeters become red zones subject to increased surveillance, restricted movement, and the constant possibility of military intervention. Citizens learn to navigate between these zones, modifying their behavior according to which set of rules currently applies.

The creation of such spatial hierarchies fundamentally alters the meaning of citizenship. In democratic theory, citizens possess equal rights to access public space and participate in civic life regardless of their geographic location within the polity. Military occupation introduces differential citizenship based on spatial position: those within secured zones enjoy greater freedom of movement and expression, while those in unsecured areas face greater restrictions and surveillance.

This spatial stratification mirrors the colonial dynamics that have characterized American imperial operations abroad. Just as occupied territories are divided into compliant zones receiving better treatment and resistant zones subjected to harsher measures, militarized American cities develop internal hierarchies based on perceived loyalty and potential threat levels. Neighborhoods with stronger support for military deployment receive lighter security presence, while areas expressing resistance face heavier surveillance and more aggressive patrols.

The Pedagogy of Submission

Military occupation functions as a form of civic education, teaching populations about their proper relationship to state authority through direct experience rather than formal instruction. The lessons are consistent whether the occupied territory is Fallujah or Ferguson: armed authority possesses ultimate legitimacy, civilian resistance is futile, and survival depends on demonstrating compliance with military directives.

These educational effects operate through what sociologists call “embodied learning”—knowledge acquired through physical experience rather than abstract reasoning. Citizens who must present identification at military checkpoints learn about their subordinate status in the political hierarchy. Residents who observe armored patrols in their neighborhoods acquire practical knowledge about the limits of civilian authority. Community members who witness military responses to public gatherings develop understanding about the acceptable boundaries of political expression.

The curriculum proves remarkably effective across different cultural contexts. Populations with no previous experience of military occupation quickly learn the behavioral norms required for survival in militarized environments. They discover which activities attract unwanted attention, which forms of movement appear suspicious, which expressions of dissent cross unacceptable lines. The learning occurs rapidly because the consequences of failure to adapt can be severe.

American populations subjected to military deployment demonstrate identical learning patterns. Citizens who initially attempt to maintain normal civic routines quickly modify their behavior based on encounters with military authority. They learn to avoid certain public spaces during patrol hours, to carry identification documents, to respond appropriately to military directives, and to monitor their own expression for potentially problematic content.

The Normalization of Extraordinary Measures

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of domestic military deployment lies in how quickly extraordinary measures become routine features of civic life. What begins as emergency response to immediate threats evolves into permanent infrastructure for managing civilian populations. The temporary checkpoints become permanent installations, the emergency patrols become regular operations, the exceptional measures become standard procedures.

This normalization process follows patterns observed in occupied territories worldwide. Military forces initially deployed for specific, time-limited objectives gradually expand their mission scope as they identify additional security requirements. Equipment brought for emergency use remains in place for ongoing operations. Personnel assigned temporary duties develop permanent institutional interests in maintaining their expanded authority.

The bureaucratic momentum proves particularly powerful in American contexts where military and law enforcement agencies compete for resources and mission relevance. Once military equipment and tactics prove effective for domestic operations, institutional incentives favor their continued use rather than their withdrawal. The extraordinary gradually becomes ordinary through administrative procedures rather than explicit political decisions.

Citizens witnessing this transformation experience what psychologists call “normalization bias”—the tendency to treat abnormal situations as normal when they persist over time. Military checkpoints that initially provoked shock and resistance become familiar features of urban landscape. Armed patrols that once seemed threatening become routine background elements of daily life. The occupied city stops feeling occupied and starts feeling normal.

Imperial Blowback and Domestic Consequences

The concept of blowback, originally developed to describe how American imperial operations abroad generate unexpected domestic consequences, applies directly to the militarization of American urban space. The techniques, equipment, and mindset developed for foreign occupation inevitably influence domestic policing when military and civilian law enforcement agencies share resources, training, and personnel.

Military veterans returning from overseas deployments bring operational experience from occupied territories into civilian law enforcement roles. They carry knowledge about population control techniques, area denial operations, and the use of overwhelming force to establish psychological dominance. While this experience can provide valuable tactical capabilities, it also imports assumptions about civilian populations that may be inappropriate for democratic policing.

The transfer of military equipment to civilian agencies through federal programs further accelerates this blowback process. Local police departments acquiring armored vehicles, military weapons, and surveillance technology inevitably adapt their operational procedures to utilize this equipment effectively. The result is the gradual militarization of routine law enforcement through equipment-driven mission creep rather than explicit policy changes.

Training programs that teach civilian officers military tactics for crowd control, building clearance, and high-risk operations complete the transformation. Police departments begin to resemble military units in their appearance, equipment, and operational methods. The distinction between foreign occupation and domestic law enforcement blurs until the same techniques used in Mosul appear on the streets of American cities.

The Symbolic Economy of Force

Military occupation operates as much through symbolic communication as through physical control. The display of overwhelming force serves psychological functions that extend far beyond immediate tactical requirements. Armored vehicles parked in prominent locations communicate state power more effectively than hidden installations. Uniformed patrols in commercial districts send stronger messages than covert surveillance operations. The visibility of military force multiplies its impact through the psychological effects of intimidation and deterrence.

American cities experiencing military deployment become theaters for this symbolic communication. The choice of equipment, the positioning of personnel, the timing of operations—all convey messages about the relationship between state and citizen that shape political consciousness as powerfully as any formal propaganda campaign. Citizens observing military operations learn about their own status in the political hierarchy through direct visual evidence rather than abstract constitutional theory.

The symbolic messages prove particularly powerful when they contradict official rhetoric about democratic values and civilian authority. When politicians speak about constitutional rights while military forces occupy civic spaces, the visual evidence overwhelms the verbal assurances. Citizens learn to trust what they see rather than what they hear, and what they see in occupied cities suggests that democratic governance has been suspended in favor of military control.

This symbolic communication operates bidirectionally. Just as military occupation sends messages to civilian populations about their subordinate status, it also communicates to military personnel about their expanded authority and mission scope. Soldiers deployed in American cities learn that civilian law enforcement has proven inadequate, that normal constitutional constraints may be suspended during emergencies, and that military solutions are appropriate for domestic political problems.

The imperial mirror thus reflects in both directions, transforming both the occupied population and the occupying force. American cities under military control begin to resemble the foreign territories where American forces have operated for decades, while American military personnel begin to see domestic civilians through the same lens they apply to potentially hostile foreign populations. The boundary between empire and homeland dissolves, replaced by a unified field of military operations where the same techniques apply regardless of geographic location or constitutional constraints.

The Collapse of the Social Contract

When military force becomes the visible guarantor of civic order, something fundamental breaks in the relationship between citizen and state. The social contract that underlies democratic governance rests on a delicate fiction: that political authority derives from popular consent rather than coercive power, that citizens participate in governance as autonomous agents rather than subjects to be managed, and that the state exists to serve the people rather than the reverse. Military occupation of civic space shatters this fiction by making visible the violence that always underlies political authority but that successful democracies keep carefully hidden.

The transition from citizen to subject occurs not through formal declaration but through the accumulated experience of living under military oversight. Citizens who must navigate checkpoints to reach their workplaces learn that their movement depends on military approval. Residents who observe armed patrols in their neighborhoods discover that their safety relies on military protection rather than community cooperation. Community members who witness military responses to public gatherings understand that their political expression occurs at the sufferance of armed authority.

These lessons reshape the fundamental assumptions that make democratic participation possible. Democratic theory assumes that citizens will engage actively in public life because they understand themselves as co-authors of the social order. Military occupation teaches the opposite lesson: that citizens are potential threats to be monitored and controlled rather than partners in governance. The psychological transformation from citizen to subject occurs through direct experience of subordination rather than abstract political theory.

The Pedagogical Function of Armed Authority

Every encounter between civilian and military authority in domestic space constitutes a lesson in political hierarchy. The citizen who must show identification at a checkpoint learns about their position in the chain of command. The resident who steps aside for an armored patrol discovers the practical meaning of right-of-way in militarized space. The community member who observes military crowd control operations receives education about the acceptable boundaries of collective action.

This educational process operates through what philosophers call “disciplinary power”—the shaping of behavior and consciousness through routine institutional practices rather than explicit coercion. Citizens subjected to military oversight gradually internalize the assumptions that justify such oversight: that they require external control to behave properly, that their autonomous judgment cannot be trusted, that their safety depends on accepting restrictions on their freedom.

The transformation proves remarkably thorough because it occurs below the threshold of conscious resistance. Citizens who would intellectually reject the proposition that they are subjects rather than citizens find themselves behaving as subjects when confronted with military authority. They comply with directives they consider illegitimate, modify their behavior to avoid unwanted attention, and accept restrictions they would normally challenge.

The disciplinary effects extend far beyond immediate encounters with military personnel. Citizens who witness military operations in their communities learn to monitor their own behavior for potentially problematic elements. They begin to see themselves through the eyes of military observers, calculating whether their activities might appear suspicious, whether their associations might seem dangerous, whether their expressions might cross unacceptable lines.

The Architecture of Paternalistic Control

Military occupation transforms the physical and social architecture of civic life from frameworks supporting autonomous citizenship into mechanisms for managing potentially dangerous populations. Public spaces designed for gathering and debate become security perimeters requiring authorization for entry. Transportation networks intended for free movement become monitored corridors subject to military checkpoint. Communication systems meant for open discourse become surveillance networks tracking potentially subversive activity.

The shift from facilitation to control reflects deeper changes in how state authority understands its relationship to the population. Democratic governance assumes that citizens possess the capacity for self-direction and that the state’s role involves creating conditions where that capacity can flourish. Military occupation assumes the opposite: that civilian populations require constant oversight to prevent them from engaging in harmful behavior.

This paternalistic logic justifies extraordinary restrictions on ordinary activities through appeals to public safety and social order. Citizens lose the presumption of innocence that democratic law enforcement traditionally maintains, becoming instead potential threats whose movements, associations, and expressions require constant monitoring. The burden of proof shifts from authorities demonstrating citizen wrongdoing to citizens demonstrating their harmlessness.

The paternalistic framework proves particularly insidious because it disguises coercive control as protective care. Military authorities present their oversight as necessary for civilian safety rather than domination. Citizens are told that restrictions on their movement serve their own interests, that surveillance of their activities protects them from external threats, that limitations on their political expression maintain social stability.

This rhetorical strategy makes resistance more difficult because it frames opposition to military control as rejection of protection rather than assertion of rights. Citizens who challenge military authority appear to be endangering themselves and their communities rather than defending democratic principles. The paternalistic logic transforms political dissent into evidence of irrationality or antisocial impulses requiring therapeutic intervention rather than constitutional protection.

The Fragility Paradox

Military occupation of American cities reveals what political theorists call the “fragility paradox”: the deployment of overwhelming force to maintain order actually signals the fundamental weakness of the political system requiring such protection. Strong governments rule through legitimacy rather than coercion, relying on popular consent rather than military intimidation. The appearance of armed authority in civic space announces that consensual governance has failed and that political order now depends on the threat of violence.

This paradox creates a self-reinforcing cycle of political decay. Military occupation undermines the social trust and civic engagement that make democratic governance possible, creating conditions that appear to justify additional military intervention. Citizens who withdraw from public life in response to military oversight leave civic space to be filled by military authority, making the militarization seem more necessary and more normal.

The cycle accelerates because military occupation changes the incentive structures that govern political behavior. Politicians who authorize military deployment gain immediate tactical advantages in managing civil unrest but lose the long-term legitimacy that comes from demonstrated ability to govern through persuasion. Military commanders who successfully maintain order through force find their institutional importance enhanced but their integration with civilian governance degraded.

Citizens caught in this dynamic face impossible choices between accepting subordination and risking confrontation with overwhelming force. The rational response for most people involves accommodation and withdrawal rather than resistance, but these individually rational choices collectively undermine the civic engagement that democratic systems require to function effectively.

The Visibility of State Violence

Democratic governance depends on what political scientists call “legitimate violence”—the state’s monopoly on coercive force that citizens accept as necessary for maintaining social order. This acceptance requires that state violence remain largely invisible in daily life, emerging only in extraordinary circumstances against clearly illegitimate threats. When military force becomes a routine feature of civic life, it makes state violence constantly visible and thus forces citizens to confront uncomfortable questions about the nature of their political system.

The visibility of military occupation in American cities destroys the comfortable fiction that democratic governments rule through consent rather than coercion. Citizens observing armed patrols, military checkpoints, and armored vehicles in their neighborhoods cannot avoid recognizing that their compliance with political authority ultimately depends on their fear of overwhelming retaliation rather than their agreement with government policies.

This recognition proves psychologically destabilizing because it contradicts fundamental assumptions about American political identity. Citizens raised to believe that they live in a free society governed by their consent must reconcile this self-image with the reality of military occupation in their communities. The cognitive dissonance typically resolves through psychological adaptation rather than political resistance: people learn to accept military oversight as normal rather than challenge the assumptions that make such oversight seem necessary.

The normalization process involves what psychologists call “cognitive accommodation”—the adjustment of beliefs and expectations to match experienced reality rather than maintaining standards that reality appears to violate. Citizens subjected to military occupation gradually lower their expectations for civic freedom, democratic participation, and constitutional protection rather than demanding that reality conform to democratic ideals.

The Erosion of Political Imagination

Perhaps the most profound consequence of urban militarization lies in its effect on political imagination—the capacity to envision alternative arrangements and believe in the possibility of different futures. Citizens living under military oversight learn to accept current conditions as inevitable rather than changeable, natural rather than political, permanent rather than temporary.

This psychological adaptation serves individual survival needs but devastates collective capacity for democratic reform. Citizens who cannot imagine alternatives to military occupation cannot organize effectively to challenge it. Communities that accept armed oversight as necessary cannot develop the social cooperation required for self-governance. Political systems that normalize military control of civilian populations cannot generate the legitimacy required for long-term stability.

The erosion occurs gradually through the accumulation of small accommodations and minor adjustments rather than dramatic moments of surrender. Citizens learn to plan their daily activities around military schedules, to modify their political expression to avoid unwanted attention, to accept restrictions they once would have challenged. Each accommodation makes the next one easier until the original expectations of civic freedom become difficult to remember or imagine recovering.

The process proves particularly devastating for younger generations who experience military occupation as their introduction to civic life rather than as a departure from previous norms. Children who grow up navigating military checkpoints, attending schools with armed security, and participating in communities under military oversight develop different assumptions about the relationship between citizen and state than previous generations possessed.

The Collapse of Democratic Time

Military occupation operates according to temporal logic fundamentally different from democratic governance. Democratic processes assume extended time horizons for deliberation, debate, and consensus-building. Military operations prioritize immediate tactical objectives over long-term political consequences. When military logic governs civic space, it imposes immediate temporal demands that make democratic participation practically impossible.

Citizens cannot engage in meaningful political deliberation while navigating military checkpoints, attend public meetings that might be disrupted by security operations, or organize community activities under constant military surveillance. The time required for democratic citizenship—the slow work of building trust, developing consensus, and creating shared commitments—becomes unavailable in environments dominated by military urgency.

The temporal collapse extends beyond immediate practical constraints to reshape expectations about political change. Citizens living under military occupation learn to focus on short-term survival rather than long-term reform, immediate compliance rather than sustained resistance, personal safety rather than collective action. The extended time horizons that make democratic politics possible disappear under the pressure of constant tactical adjustments to military oversight.

This temporal compression proves particularly destructive to political movements that challenge existing arrangements. Social change requires sustained organization, patient coalition-building, and persistent pressure on political institutions over extended periods. Military occupation makes such sustained political action practically impossible by forcing all political energy into immediate responses to tactical situations rather than strategic planning for systemic change.

The occupied American city thus represents more than a temporary security measure or emergency response to immediate threats. It embodies a fundamental transformation in the relationship between state and citizen, from partnership in democratic governance to hierarchy in military control. The symbols of force that appear in civic space carry meanings that extend far beyond their immediate tactical functions, reshaping political consciousness in ways that may prove more consequential than whatever specific crises prompted their deployment.

When the instruments of external war appear in the heart of the polis, they announce that the democratic experiment has entered a new and potentially terminal phase. The citizen-soldier who once embodied democratic ideals gives way to the professional military force that treats all civilians as potential enemies. The civic square that once hosted democratic debate becomes the militarized zone where authority displays its power through the threat of overwhelming force. The social contract that once defined American political identity dissolves into the raw relationship between occupier and occupied, leaving behind the question of whether democratic governance can survive its own abandonment by those sworn to protect it.