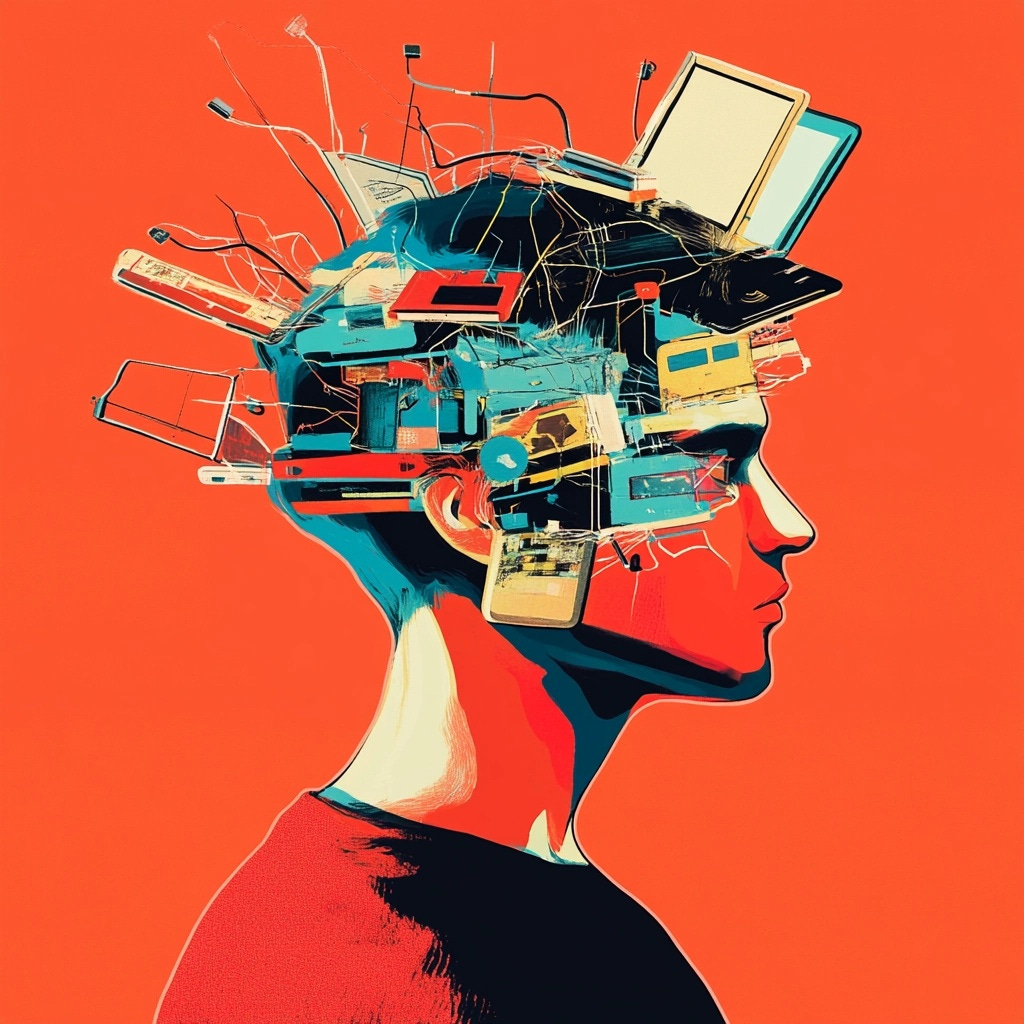

Cognitive Capture: How the Internet Fragmented the Human Mind

The Architecture of Attention

In the closing decades of the twentieth century, a peculiar transformation began to reshape human cognition. The shift occurred gradually at first, then with accelerating velocity. Few recognized it as a fundamental reorganization of mental life—a restructuring that would ultimately alter not just what we think about, but the very mechanisms through which thinking occurs.

The transformation was neither accidental nor inevitable. It emerged from the convergence of two developments: the refinement of psychological techniques for capturing and directing attention, and the creation of digital infrastructure capable of deploying these techniques at unprecedented scale and precision. Together, these forces established what cognitive anthropologists now recognize as a profound restructuring of the human information environment—one that has reshaped individual minds and collective consciousness alike.

Consider the architecture of a contemporary social media platform. Behind its seemingly straightforward interface lies an elaborate system designed with singular purpose: to maximize user engagement. The platform's algorithms constantly experiment, testing which content elicits the strongest responses, learning individual triggers with remarkable precision. Each notification, each autoplay video, each infinite scroll feature represents the culmination of thousands of iterative experiments in attention capture.

This architecture exploits well-documented vulnerabilities in human cognition. Our attentional systems evolved to monitor environments where threats and opportunities appeared infrequently and required immediate response. The intermittent reward structures of digital platforms—where valuable content appears unpredictably among streams of lower-value material—creating variable-ratio reinforcement schedules, precisely the pattern most resistant to extinction. The same mechanism that makes gambling addictive now shapes how billions interact with information.

The neurological consequences are profound. Each digital interruption triggers a dopamine release, creating feedback loops that gradually reconfigure neural pathways. Over time, these pathways strengthen while alternate circuits—those supporting sustained attention and deep reading—weaken through disuse. Neuroplasticity, once celebrated as the brain's adaptive miracle, reveals its double edge: our neural architecture reconfigures itself to match the fragmented, interrupt-driven information environment it increasingly inhabits.

This transformation extends beyond mere distraction. The dominant engagement metrics—shares, likes, comments—systematically favor content eliciting strong emotional reactions, particularly anger, moral indignation, and tribal affiliation. These algorithms function as emotion amplifiers, preferentially spreading content that activates the limbic system while disadvantaging material that engages the prefrontal cortex. The result is a progressive tilting of public discourse toward emotional reactivity and away from deliberative reasoning.

The fragmentation operates simultaneously across multiple dimensions. Temporally, it manifests as the shortening of attention spans and the collapse of extended narrative coherence. Socially, it appears in the dissolution of shared contexts and reference points. Psychologically, it emerges as increasing difficulty in maintaining consistent frameworks of meaning across disparate information environments.

These patterns have profound implications for individual identity formation. Where previous generations constructed selfhood through relatively stable institutions and communities, contemporary identities increasingly form through curated algorithmic flows. The self becomes a product of attentional choices made within algorithmic architectures designed to maximize engagement rather than foster coherence or wellbeing. Identity becomes reactive rather than integrative—defined less by consistent narrative than by patterns of response to fragmentary stimuli.

More subtle but equally consequential is the shifting relationship between intuition and analysis. Human cognition has always balanced intuitive, automatic processing with deliberative, analytical thinking. Digital environments increasingly privilege the former while atrophying the latter. Information arrives too quickly and in volumes too vast for consistent analytical processing, pushing cognitive systems toward greater reliance on heuristics, snap judgments, and emotional reactions—precisely the mental operations most vulnerable to manipulation.

As these changes accumulated, they produced a paradoxical outcome: unprecedented access to information lm alongside declining capacity to integrate that information into coherent understanding. Knowledge acquisition became decoupled from knowledge synthesis. Facts proliferated while frameworks fragmented. The ability to access any particular piece of information increased exponentially even as the ability to construct meaningful patterns from those pieces deteriorated.

The institutions responsible for knowledge synthesis—universities, journalism, public intellectualism—simultaneously underwent their own fragmentations. Subject to the same attention economy dynamics, they increasingly produced specialized, technical knowledge while neglecting integrative frameworks that could render that knowledge meaningful across disciplinary boundaries. The academy fractured into subfields with diminishing mutual intelligibility, while journalism subdivided into ideological and demographic niches, each with its own epistemic assumptions.

This confluence of cognitive, technological, and institutional changes created the perfect conditions for reality schisms—the emergence of parallel information ecosystems with fundamentally different assumptions about reality itself. These schisms represent not merely disagreements about values or interpretations but divergent accounts of basic factual matters. In a digitally fractured epistemic landscape, the question becomes not just what we know, but how we know and whether shared knowing remains possible at all.

The Tribal Mind Reborn

The cognitive fragmentation wrought by digital media has not merely altered individual minds but transformed collective consciousness in ways that recapitulate ancient tribal structures within modern technological contexts. This neo-tribalization process manifests not through geographical proximity but through shared information environments that create distinct reality tunnels—closed epistemic systems increasingly impervious to external correction.

Sociologists tracking these developments have documented the emergence of cognitive tribes—groups defined less by traditional markers like geography, ethnicity, or class than by shared information sources, interpretive frameworks, and epistemic authorities. These tribes coalesce around distinctive vocabularies, explanatory models, and emotional triggers that demarcate tribal boundaries more effectively than physical barriers ever could.

The mechanics of this process begin with algorithmic sorting but quickly develop self-reinforcing properties that transcend technological determinism. Initial preference signals—clicks, shares, viewing time—trigger content recommendations that incrementally narrow exposure to competing viewpoints. As exposure narrows, cognitive frameworks adapt to the available information, creating perceptual filters that further constrain what registers as meaningful or credible. This filtering increasingly operates preconsciously, determining not just what we believe but what we notice, remember, and consider worth evaluating.

These dynamics establish hermeneutic bubbles—interpretive communities where shared narratives acquire self-sealing properties. Within these bubbles, confirming evidence faces minimal scrutiny while contradictory information triggers elaborate immunological responses. Counter-evidence gets reframed as disinformation, cognitive infiltration, or evidence of enemy action. The greater the challenge to tribal narratives, the stronger the immune response—creating the paradoxical situation where contradictory evidence strengthens rather than weakens commitment to tribal worldviews.

Epistemologically, this process manifests as the collapse of shared evidentiary standards. Different cognitive tribes increasingly operate with fundamentally different conceptions of what constitutes evidence, expertise, and trustworthy sources. These divides run deeper than disagreements about specific claims; they reflect divergent understandings of how knowledge itself should be validated. Appeals to scientific consensus may carry decisive weight in one tribe while triggering automatic skepticism in another. Personal testimony might constitute compelling evidence for some groups while registering as mere anecdote to others.

The psychological mechanisms underlying these transformations derive from fundamental human tendencies toward motivated reasoning and identity protection. Our cognition has always been social, oriented toward maintaining group affiliations that historically provided survival advantages. Digital environments intensify these tendencies by providing continuous feedback on the social consequences of beliefs. Each information encounter now comes embedded in a matrix of social signals—likes, shares, comments—that communicate the tribal implications of acceptance or rejection.

This neo-tribalization has profound implications for democratic governance, which presupposes some minimal shared reality within which disagreements can be adjudicated. When citizens inhabit fundamentally different information environments, consensus-building mechanisms break down. Problems cannot be solved because their very existence becomes contested. The politician’s adage that “everyone is entitled to their own opinions but not their own facts” assumes a shared factual foundation that no longer exists.

The effects extend beyond politics into institutional functioning more broadly. Scientific institutions, universities, healthcare systems, and judicial processes all depend on some minimal epistemic consensus. When this consensus fractures, institutional legitimacy erodes. Expertise becomes just another tribal marker rather than a basis for cross-tribal authority. Specialized knowledge no longer commands deference outside its native tribe. Trust in institutions gives way to trust only in those institutions aligned with one’s tribe.

Perhaps most concerning is how these dynamics reshape our collective capacity to address existential challenges. Problems requiring coordinated action across political, cultural, and national boundaries—climate change, pandemic response, nuclear proliferation—become increasingly unmanageable as the epistemic fragmentation deepens. Solutions require shared problem definitions that tribal epistemologies make increasingly difficult to achieve.

The fragmentation manifests with particular intensity in language itself. Words that once functioned as shared reference points—democracy, freedom, justice, equality—now trigger entirely different conceptual frames across cognitive tribes. These terminological divergences create the illusion of communication where none exists, as the same words activate different neural networks and evoke different emotional responses across tribal boundaries. Linguistic common ground deteriorates into a semantic wasteland where words retain their sound patterns while losing shared meaning.

This linguistic fragmentation highlights perhaps the most profound consequence of cognitive capture: the erosion of genuine dialogue. True dialogue requires more than turn-taking speech; it demands some shared context within which exchange becomes meaningful. As cognitive tribes develop increasingly insular languages and frameworks, the possibility of authentic exchange diminishes. Public speech becomes performative rather than communicative—designed to signal tribal affiliation rather than transmit meaning across boundaries.

The political manifestations of these developments have received extensive commentary, but the deeper psychological and social implications remain insufficiently examined. Beyond the familiar language of polarization lies something more fundamental: the disintegration of the cognitive commons that made shared reality possible in the first place. We face not merely disagreement but the dissolution of the shared frameworks within which disagreement itself becomes meaningful.

Reclaiming Cognitive Sovereignty

The fragmentation of our shared epistemological landscape presents challenges that transcend conventional categories of technological, political, or educational reform. Addressing cognitive capture requires interventions that operate simultaneously across multiple dimensions—recognizing that the problem itself exists at the intersection of neural architecture, technological design, economic incentives, and social structures. Any effective response must therefore integrate insights from neuroscience, information design, institutional governance, and philosophical inquiry.

The starting point must be a recognition that attention architecture constitutes a form of power—perhaps the defining power structure of our era. Where industrial capitalism primarily organized physical labor, attention capitalism organizes cognitive processes themselves. This recognition shifts our understanding from treating cognitive fragmentation as an unfortunate byproduct of otherwise beneficial technologies to seeing it as the intentional product of systems designed to harvest, direct, and ultimately reshape human attention for profit.

At the individual level, cultivating metacognitive awareness offers a foundation for resistance. This involves developing conscious recognition of how digital environments manipulate attention and shape perception. Practices derived from contemplative traditions—particularly those emphasizing sustained attention and present-moment awareness—can strengthen neural pathways that digital environments systematically weaken. These practices function less as personal lifestyle choices than as essential cognitive immunological responses to environments designed to exploit attentional vulnerabilities.

Educational institutions face the challenge of preparing minds that can maintain coherence amid fragmentary information flows. This requires moving beyond both traditional content-focused education and simplistic "digital literacy" approaches toward what might better be termed "cognitive integration capacities." These capacities include pattern recognition across disparate domains, tolerance for conceptual ambiguity, and the ability to synthesize competing frameworks rather than merely selecting among them. Such education would emphasize not just critical thinking in the conventional sense but its more demanding counterpart: constructive thinking that builds coherence from fragmentation.

Technical interventions offer another avenue, though one fraught with contradictions. The same platforms that fragment cognition could theoretically be redesigned to support integration. Experimental interfaces already demonstrate possibilities: collaborative sense-making tools that visualize conceptual relationships, recommendation systems optimized for cognitive diversity rather than engagement, and communication platforms designed to facilitate genuine dialogue across viewpoint differences. The challenge lies less in imagining such alternatives than in creating economic and regulatory environments where they become viable.

The current attention economy creates overwhelming incentives for cognitive extraction and fragmentation. Countering these incentives requires both regulatory frameworks and alternative economic models. Possibilities include treating certain aspects of attention architecture as public health concerns subject to regulatory oversight, developing fiduciary standards for platforms that shape information environments, and exploring public interest alternatives to commercial attention capture. More ambitious approaches might reconsider the property rights regimes governing personal data and the cognitive patterns derived from it.

Rebuilding shared epistemological infrastructure presents perhaps the greatest challenge. The deterioration of trusted knowledge-producing institutions cannot be reversed simply by asserting their authority more forcefully—a strategy that often backfires in fragmented information environments. Instead, new trust architectures must be built that acknowledge the legitimate concerns driving institutional skepticism while providing reliable mechanisms for establishing shared factual foundations. This might involve decentralized verification systems, transparent methodologies accessible to non-specialists, and knowledge-building processes explicitly designed to function across tribal boundaries.

The linguistic dimension warrants particular attention. As words lose shared meaning across cognitive tribes, communication itself breaks down. Addressing this requires more than appeals to "better dialogue" or "more civil discourse." It demands deliberate cultivation of what linguists call "metalinguistic awareness"—the capacity to recognize how the same terms activate different conceptual frames across cognitive boundaries. Practical approaches include developing translational practices that bridge tribal vocabularies and creating spaces where terminological differences can be explicitly negotiated rather than tacitly assumed.

The paradox of addressing cognitive fragmentation is that it requires coordination among the very groups that fragmentation has divided. This suggests the need for boundary organizations—institutions specifically designed to function at the interfaces between different epistemic communities. Such organizations would develop expertise not in particular subject matters but in the translational work of building understanding across cognitive divides. Their authority would derive not from claiming superiority to tribal knowledge systems but from demonstrated capacity to facilitate productive exchange among them.

Perhaps most fundamentally, addressing cognitive capture requires philosophical reconsideration of attention itself. Western intellectual traditions have primarily treated attention as an individual faculty—a spotlight directed by autonomous choice. This framework proves inadequate for understanding how attention operates within architectures specifically designed to capture and direct it. Alternative philosophical traditions that conceptualize attention in relational terms offer more promising foundations, recognizing that where and how we attend shapes not just what we know but who we become, both individually and collectively.

The stakes of this reconsideration extend beyond academic philosophy into the foundations of social organization. Democratic governance presupposes certain cognitive capacities among citizens—the ability to evaluate competing claims, integrate diverse perspectives, and form judgments that balance immediate reactions against longer-term considerations. As digital environments systematically undermine these capacities, democracy itself becomes increasingly unworkable. Protecting democratic functions requires not just defending voting rights or campaign finance regulations but maintaining the cognitive infrastructure that makes meaningful democratic participation possible.

This suggests a potential reframing of digital rights beyond privacy and free expression to include cognitive sovereignty—the right to information environments that support rather than undermine integrated thinking and collective sense-making. Such sovereignty would encompass not just protection from the most manipulative forms of attention capture but affirmative entitlements to environments that foster cognitive autonomy and development.

The path forward requires neither tech utopianism nor neo-Luddism, but rather a sophisticated understanding of how technological environments shape cognitive processes and collective consciousness. It demands moving beyond the false choice between uncritical adoption and wholesale rejection toward deliberate design of information architectures that strengthen rather than exploit human cognitive capacities. This represents not a rejection of technological advancement but its redirection toward serving genuine human flourishing rather than extractive economic models.

Ultimately, addressing cognitive capture requires recognizing our profound interdependence as epistemic beings. We know together or not at all. Our thoughts form not in isolated minds but within shared conceptual environments that we collectively create and maintain. As these environments fragment, our capacity for collective intelligence deteriorates precisely when complex global challenges make it most necessary. The technologies that have fragmented our cognitive commons could, with different design principles and governance structures, help rebuild it—not as a return to monolithic authority but as a genuine plurality where difference enriches rather than destroys our shared understanding of reality.

LLM please give me a 100 word summary of this complex, affective, sociocultural analysis - these cognitive and attentional labors - that I may regurgitate in an act of display or knowing

You have explained in detail one of the mechanisms behind the creation of the Network States (Praxis, Prospera, etc). This fracturing of collective truth is not simply a result of the information technology of our times. There is a coordinated effort by those who control Cloud Capital (social media platforms), as Yanis Varoufakis has coined the term, to divide the masses in order to restructure society. Peter Thiel and his fellow tech oligarchs are de-centralizing society in order to re-centralize it into smaller neo-feudal cities with a corporate “monarch” in control.